01/ THE DISCOVERY OF THEATRE; and ‘AUTODRAMMA’

The ‘Poor Theatre’ of Monticchiello is a social and cultural project which dates from the 1960s.

At the beginning of that decade, this Tuscan village was going through a profound upheaval, arising from the sudden collapse of the economic and social system which had characterized its existence for centuries: the system of sharecropping (mezzadria). The work structures, culture and traditions which belonged to that system were rapidly disappearing, and the population was being halved. Those who were left behind, whether by choice or by necessity, began to reflect on the meaning of the rapid transformations which were devastating their world and their identity.

In a village which had no theatre building, it was decided to focus around an idea of open-air theatre in the public square: a performance choice which soon became an attempt by the people to create on stage an account of their own lives. A way of resisting the upheaval.

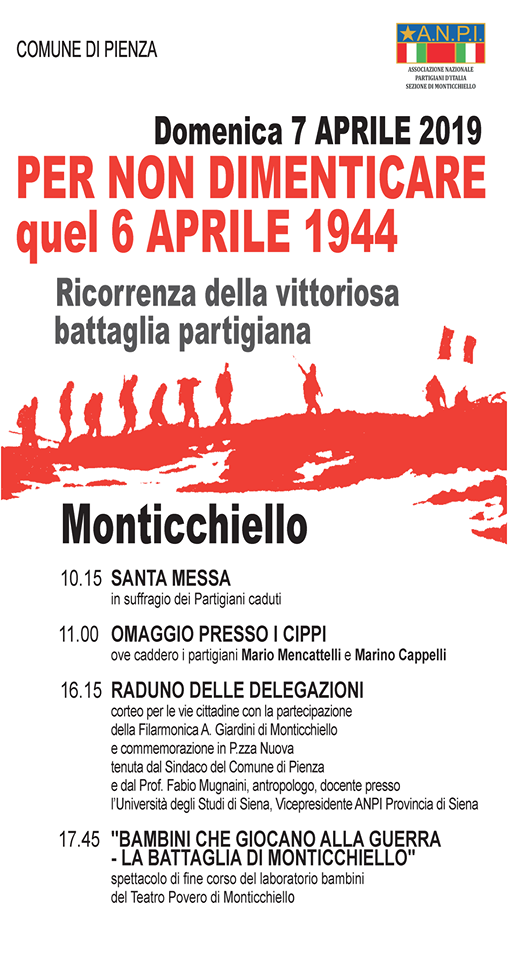

The first shows, between 1967 and 1969, began by stressing the community’s ability to resist the threats which in the course of history had put its very existence at risk: invasions by foreign armies, major episodes of popular resistance…

Also in these early years there began to emerge a very particular methodology for putting a show together: a process involving full participation. Meetings of the villagers and the members of the theatre company were held over a period of months: they conducted a dialogue with a smaller select group, which was charged with turning the suggestions made by the meetings into theatrical projects.

Every one of the company’s shows was performed only for one season. The number of performances per year increased very quickly, in response to public and critical demand. Equally quickly, other characteristics became definable, including a unique relationship between actor and stage character: very often the actors in the square were ‘playing themselves’. Also, from the early 1970s on, narrative episodes in the plays were alternated with meta-theatrical moments, sometimes based on direct address and dialogue with the audience.

Attention was soon focused on the central theme of rehabilitating the cultural and social identity of the peasant class, which for centuries had been treated with contempt by other social groups. The peasant world was explored in a way which avoided romanticized stereotypes, and was set against the new types of social identity which were emerging in the twentieth century. In Monticchiello, as elsewhere, sharecroppers were disappearing and making way for small-scale independent farmers, industrial workers, clerks, etc.

In these early years the plays settled into a regular three-act structure, in which a single theme was explored in relation first of all to the village’s past and then to the present, and finally subjected to discussion and debate in the light of how things had changed over the years.

During the same period, the non-professional actors of Monticchiello established their own particular acting methods: without reference to any academic theatrical format, they developed styles of expression which were linked to long-established popular traditions of orality. The most gifted performers became, in all but name, ‘professional’ projectors of themselves, some discovering that they possessed a striking communicative ability. Even with its small numbers, the community was able to present a broad range of characters for the stage.

Initially the Teatro Povero did make use of some outside professional expertise, in an encounter which gave birth to a genuinely participatory dramaturgy. Significant names include Mario Guidotti, who drafted the scripts and called himself ‘Monticchiello’s notary’; and Arnaldo Della Giovampaola, the director who created the performances in the 1970s and was the first to offer original solutions to the problems raised by staging shows in the village square.

Among the various definitions which were offered to encapsulate Monticchiello’s special theatrical formula, the word which slowly took root was the one proposed by the international theatre director Giorgio Strehler: ‘autodramma’. This was the label which the company made its own. For years now, as subtitle to each individual show, there has appeared the phrase ‘Autodramma conceived, composed and staged by the people of Monticchiello’.

02/ FROM THE 1980s TO THE NEW CENTURY

Second-stage autodramma: dealing with complexity

The organizational structure which the Teatro Povero chose, once it reached relative maturity, was that of the cooperative: in 1980 there came the formal constitution of the Cooperative of the Poor Theatre of Monticchiello, which also involved itself increasingly, over time, with running social and support services for the community.

On the theatrical side, many changes took place, starting with a revised internal structure. For the conception and realization of the plays, a communication circuit was set up between at least three groups: the meetings of the whole company/community; the actors; and then a smaller executive group which held ‘closed meetings’ (assemblee ristrette). This last group had the task of turning ideas offered by the open meetings, and by the actors, into outlines of plays and then into full scripts. A central co-ordinating figure in all this was Andrea Cresti, one of the founders of the whole project: from 1981 onwards he was the director of all the Teatro Povero’s summer productions, and the person who supervised most closely the transformation of outline summaries into scripts.

The shows produced in the 1980s and 1990s followed a slow but definitive passage away from the original thee-act format, towards a single act with no interval. By now the plays were built less around precise motions to be debated. The change reflected an increasing mistrust of purely rational structures, in which a calm formal debate was pursued around a stated theme. What was now offered on stage was enriched by new elements: a spirit of grotesquery, and an often rueful taste for the absurd. There were fewer coherent frameworks in terms of ideas, time, space and setting; and the scenography moved towards more complicated sets which were both evocative and mysterious.

In terms of subject-matter, there was still regular focus on large-scale themes which had resonance within the village’s life: complex environmental issues; renewed wars, especially in the Gulf; the commercialization of moral values; confrontations with people who are ‘different’, in the contexts both of mental illness within society and of migration from outside. On the one hand there was a constant reference back to the world of peasant sharecroppers, which provided a stock of experiences, feelings, stories and values; but on the other hand there was no claim that this heritage could offer easy answers or solutions. At the most it could provide signposts, which could be used to avoid entirely losing one’s way in stormy weather…

This feeling of uncertainty did however lead to a new dramatic mechanism, which drew energy from rediscovering some traditional theatrical solutions. The peasant class, which had lived for centuries in a state of subordination to other social groups, had been able to get its own back through certain forms of popular traditional theatre. Most of all through formats based on a carnival dimension, presenting a ‘world upside down’: a world in which it was their turn to poke fun at their ‘superiors’—at shopkeepers, lawyers, doctors, policemen… The relief offered by this mechanism was of course temporary and ephemeral; but in such a subversive reversal of roles, even if it lasted only for the duration of a folk tale or performance, there was a germ of aspiration, hope for more cultural and social equality, which would later assume a more concrete and articulate form. Where reason can only see obstacles to progress, imagination can construct a more decisive alternative. And so in the Teatro Povero there was beginning to appear a new fantastical dimension: the challenge that can be produced by poetic imagination.

03/ THE FIRST YEARS OF THE MILLENNIUM

New opportunites, new threats

In the years after 2000, the Val d’Orcia has become very different from what it was in the 1960s. From being a marginalized territory on the verge of depopulation, it has gone through a major re-evaluation in cultural, economic and social terms. It was designated as a World Heritage Site in 2004; and with the rise in the number of visitors, the area can be seen as undergoing a second transformation, after the first one linked to the collapse of sharecropping. The first years of the new century have in general been a period marked by hope, and by expectations for development and progress.

Until 2007, Monticchiello’s autodrammi took account of these changes, though they also reflected the concerns which came with them: a fear of being turned into a ‘living museum’, of becoming ‘performers’ in a negative sense; the need to offer a balanced view, rather than a stereotyped idyllic picture, of their own peasant past; the difficulty in maintaining a genuine dialogue with younger people, and of actively including them in the ongoing social and cultural project. With the passing of the generations, the threads which linked back to the peasant-sharecropping past were becoming more and more tenuous; but efforts were still made to keep those memories alive, with their challenges and issues, as the landmark fortieth year approached. During this period the Teatro Povero Co-Operative opened the Tepotratos Museum (dedicated to Tuscan popular theatre), and it launched a number of enterprises from its office: a bookshop and news stand, a tourist bureau, an internet café, a collection service for medical prescriptions, a library, a general store…

The year 2007 was then a crisis year for Monticchiello and its theatre. A proposed new construction project on the edge of the village sparked a wide public debate, initially just within the community but in the end also on a national scale. The company decided that its autodramma that summer would offer reflections, not so much on alternative views of the question itself (which had divided Monticchiello in a way not experienced before), but rather on the the pressures which had been exerted on the village by the publicity given to the issue.

04 / AFTER 2008

The crisis, on a large and small scale

The most recent productions of the Teatro Povero have tended to address the repercussions of the crisis which began in 2008, now defined as not simply economic but also social and political in the broadest sense. During these years the problems of the young generation in finding both work and social identity, and the problems of a whole community crushed by the weight of economic difficulties, have been represented alongside a resentful picture of no-longer-ruling classes: we have seen satirically stylized depictions of figures who exercise power, but who seem incapable of managing any kind of change, and who seem indeed to be grotesque and predatory, working only in their own interest. In the face of all this, the business of mounting a summer spectacle has become an opportunity to express a shared desire for change, to give these feelings a dramatic shape, to nurture a hope that even the subversive fantasies of a small community can reveal glimpses of a path towards a better future.

original text by Gianpiero Giglioni

English version by Richard Andrews