The autodrammi of Monticchiello had often commented ironically on confrontations between its apparently secure little world and the more brutal aspects of modernity which lay—perhaps—beyond the horizons of the Val d’Orcia. In 2007, however, the imagined ‘invasions’ of that outside world ceased to be contemplated metaphorically with reference to the siege of 1553, and became an uncomfortable reality. The proposed construction of a new set of houses on the side of the village’s hill were blown up into a major national controversy, bringing a flood of very unwelcome media attention, and causing deep divisions within the village of a type which had not been experienced before. On one side there were hopes that new life, and new residents, could be brought to revive a fading community; on the other side the new houses were seen as an ugly, even ‘monstrous’, intrusion into a protected UNESCO zone.

Autodrammi had always aimed to express the real current preoccupations of Monticchiello, and it was hard to contemplate a 2007 show which did not address the issue of the ‘new houses’. It was also very difficult to face the question in public without provoking and deepening existing antagonisms. The show had to tread a very delicate line between being tactful and being honest. It was noted that the new houses were to be built on what had once been a communal threshing ground, or aia; that word now sounded rather like a cry of pain (ahi!), and this provided the composite title.

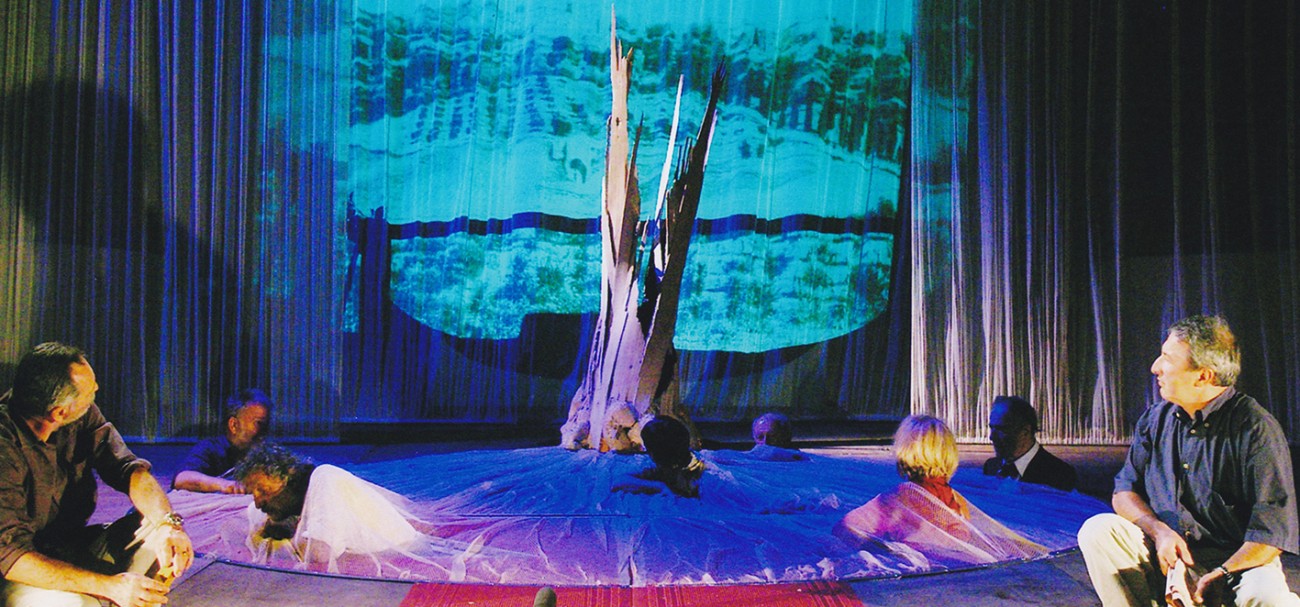

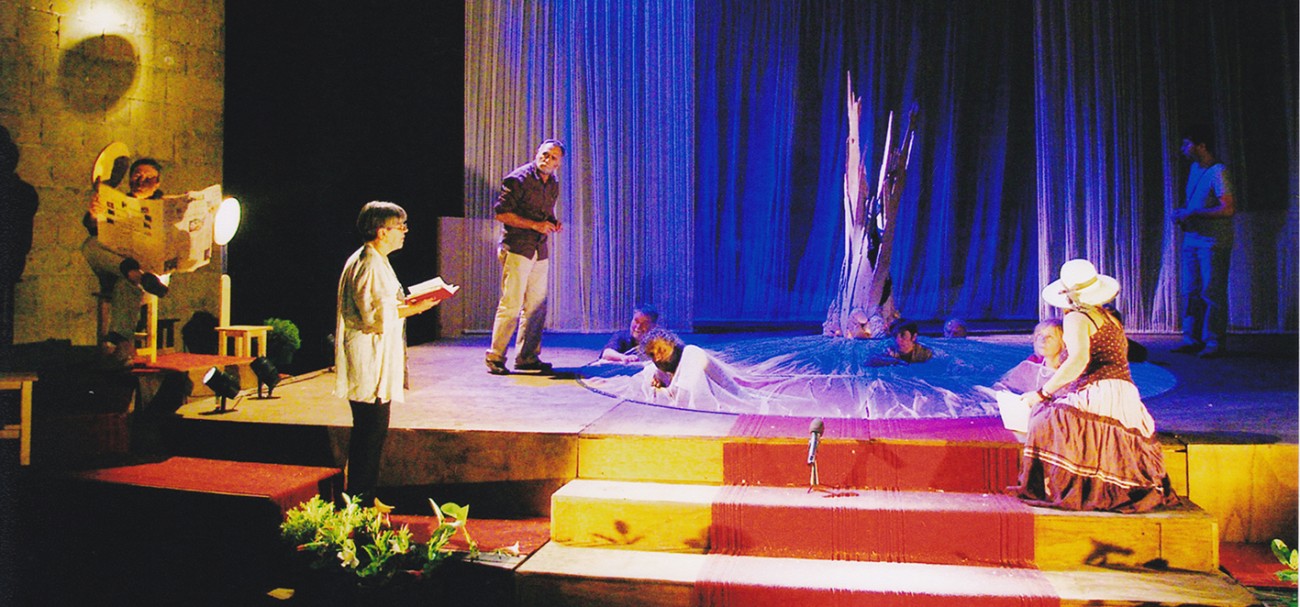

The central conceit of the play was to show Monticchiellesi as uncommunicative ‘monoliths’, trapped by circumstances within a chalk circle, and resistant to the attentions of passing tourists (as they had been resistant to journalists in the preceding months). There were careful allusions to the controversy of the ‘new houses’, and also to the question of whether the village should express its feelings on stage. Reference was made by contrast—not for the first time, in this theatre—to the solidarity of the old peasant community in the face of exploitation and eviction.

However, in order to ‘distance’ the whole script a little, and in order not to open too many wounds, these metaphorical allusions were framed by something apparently less relevant and less controversial: the performance of a sarcastic one-act farce by Chekhov called The Wedding. This had been the comfortable entertaining play which the company had mounted a few months earlier, as its Christmas show. If there was any relationship between the two separate components of A(h)ia!, the audience had to deduce it.