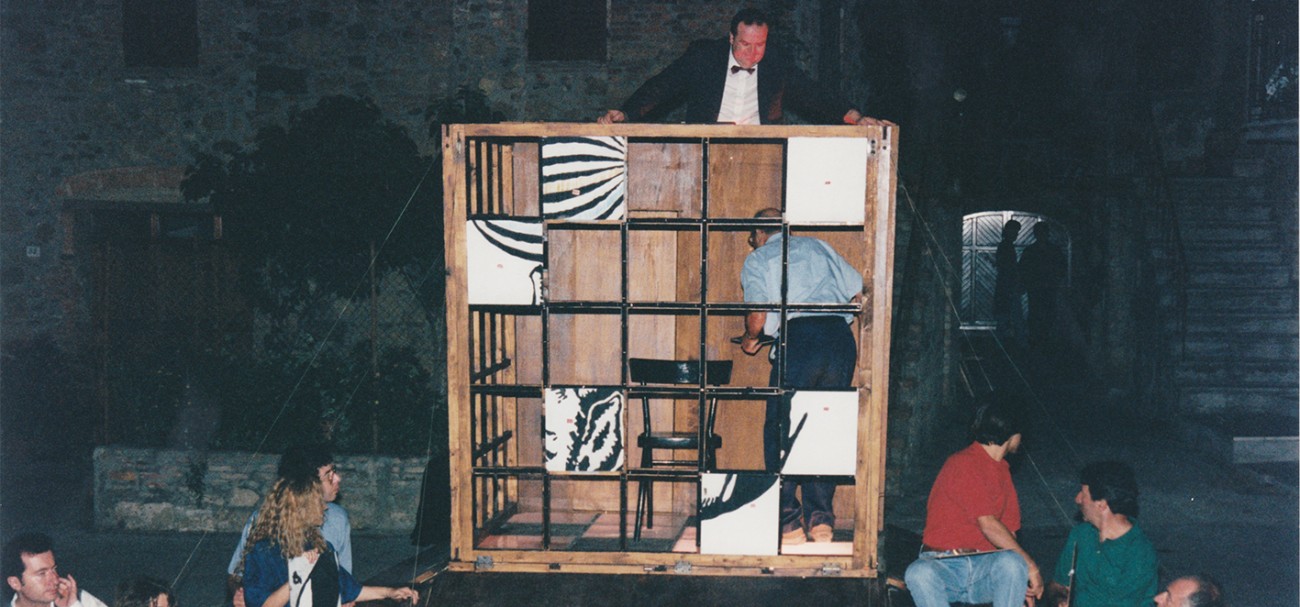

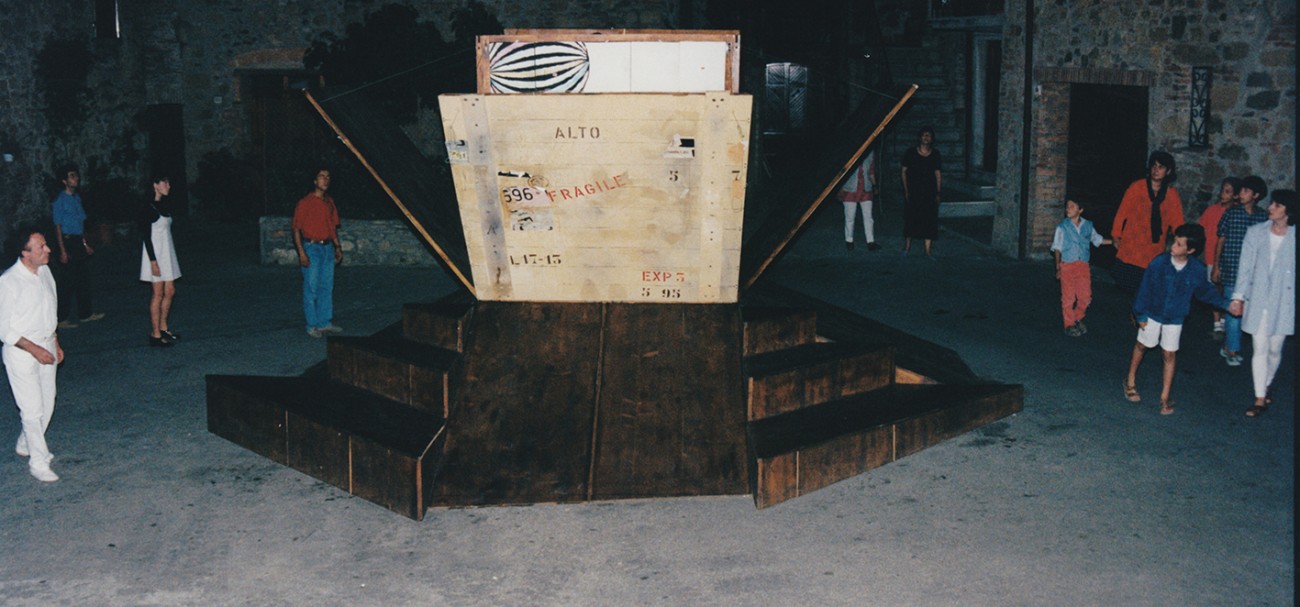

Not for the first time (one thinks also of 1984), the Teatro Povero confronted the theme of gambling and games, in modern society and in the past. It was recognised that the tendency to dream of a stroke of good luck, which might resolve all one’s problems for ever, was an ineradicable aspect of human nature. But the ‘modern’ part of this autodramma took to ridiculous fantastic extremes the contemporary vogue for game shows and competitions in which major prizes might be won—or lost. The village was depicted as being invaded and overwhelmed by a perennial game in which the permission to act, or the prohibition of action, was determined by one’s ability to answer a series of random quiz questions. In extreme cases, participants were condemned to a state of ‘game death’ (morte ludica), in which they were deprived of all civil rights and even of a consistent identity.

Then, going back to the late 1950s, families of Tuscan peasants were seen returning from the annual fair, which (by the standards of that time) had also presented them with purchases and prizes which seemed to raise them above the conditions of ordinary life. The man who thought he was smarter than everyone else had been persuaded to buy a product which was totally useless. Worst of all, the unfortunate peasant Alizzardo (who never appeared on stage) had bet his whole family livelihood on the three-card trick—and lost. Parallels were made between the ‘marked cards’ used by the professional trickster and the deceits practised on the peasant class at that time, in their political battle with the landlords over possession of the land.

Back in the modern world, the manipulative game and its presenter were attacked and destroyed by the villagers; but then seemed slowly to be growing back again, like mushrooms.