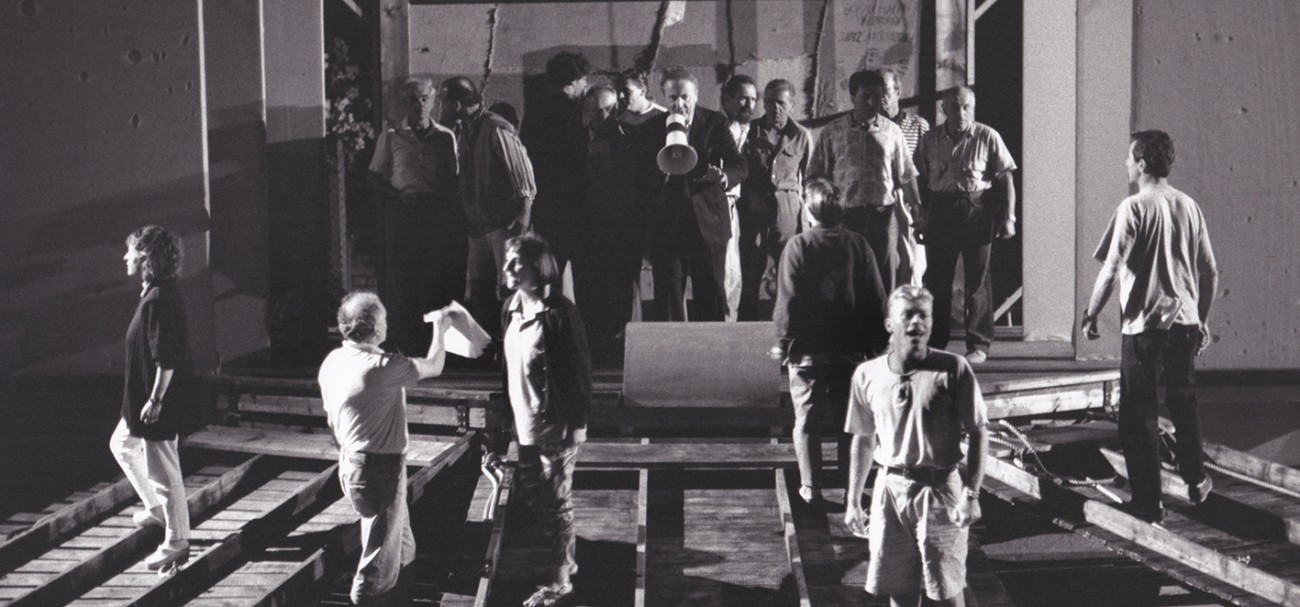

Sfratti was a landmark production in many ways. It ended of the habit of playing in two acts with an interval, in favour of a more concentrated one-act structure which has remained the norm ever since. It was also the first of many plays in which the Teatro Povero began to examine the value and function of autodrammi themselves, questioning particularly the company’s own insistence on reviving memories of a peasant experience which might now be consigned to history.

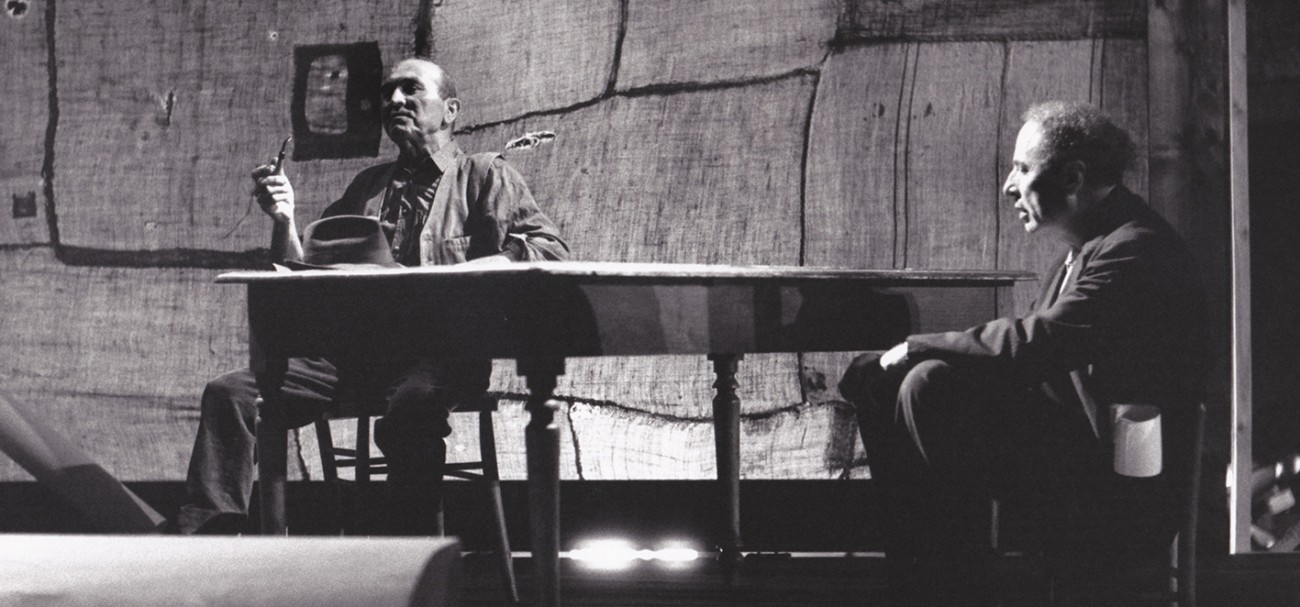

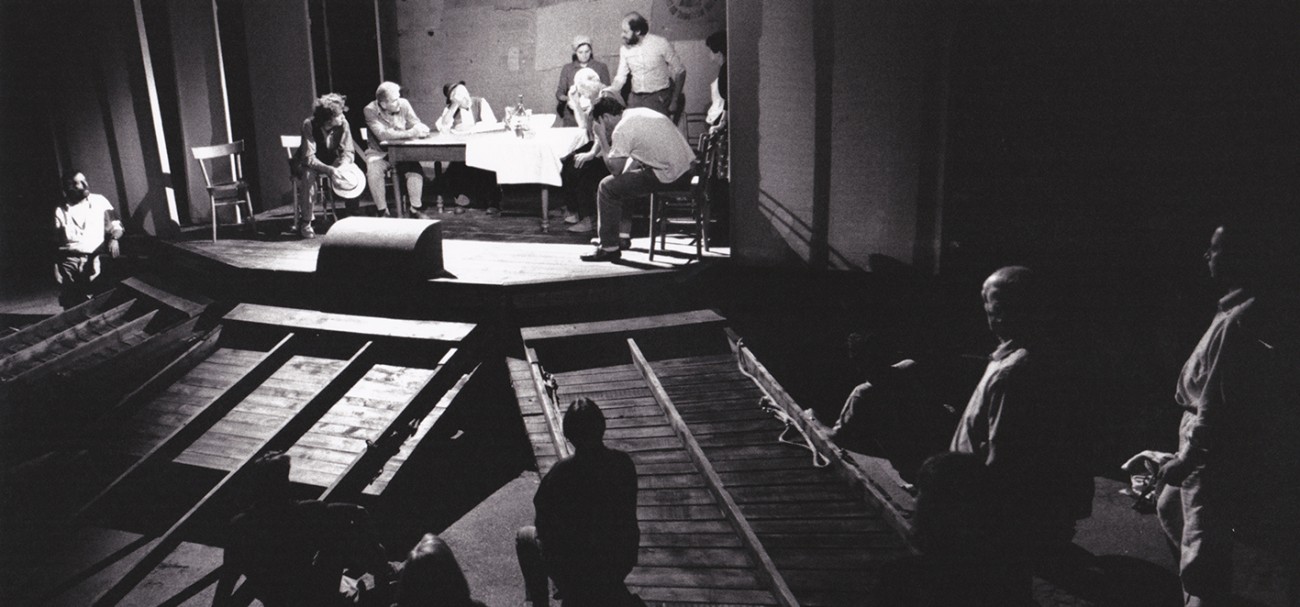

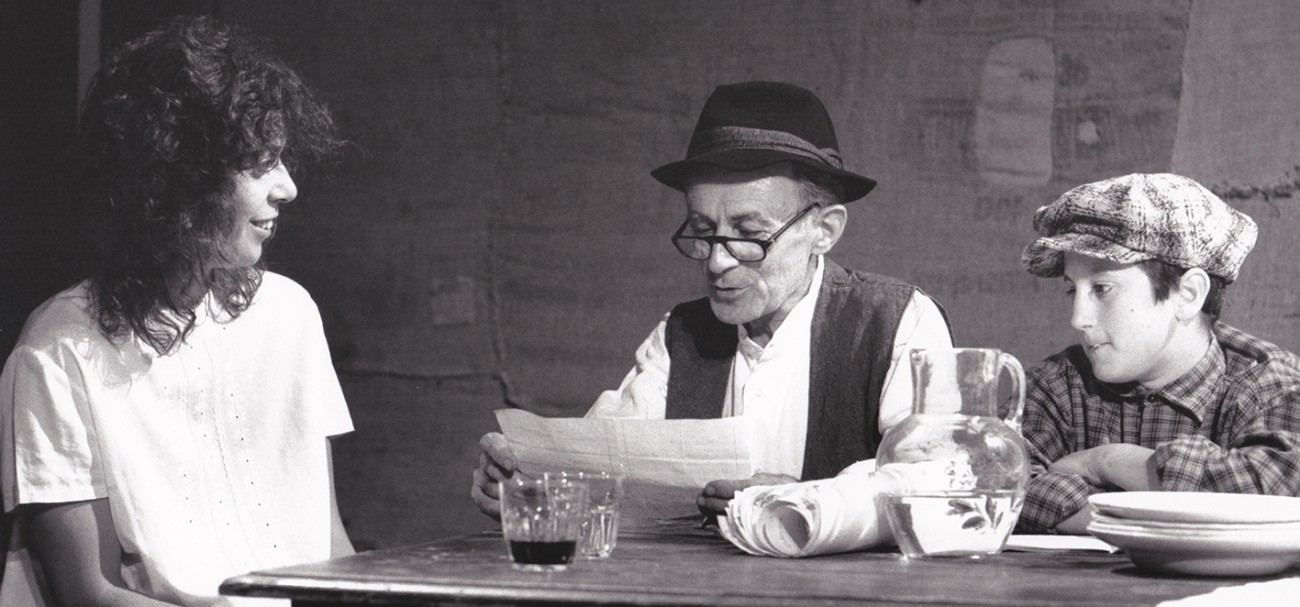

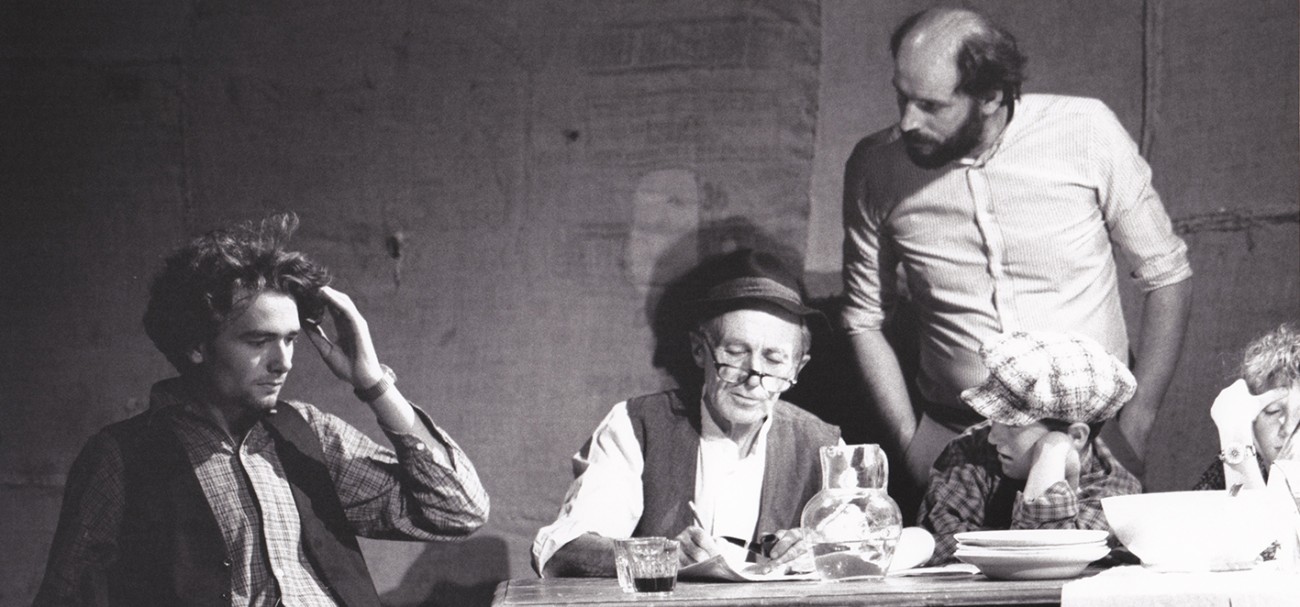

On a ‘stage within the stage’, a drama was enacted about a sharecropping family which faced eviction, homelessness and unemployment. The action was interleaved with readings from a historical chronicle, describing how Tuscan peasants reacted with collective solidarity against acts of oppression —the ‘Eviction’ of the title—by the landowners.

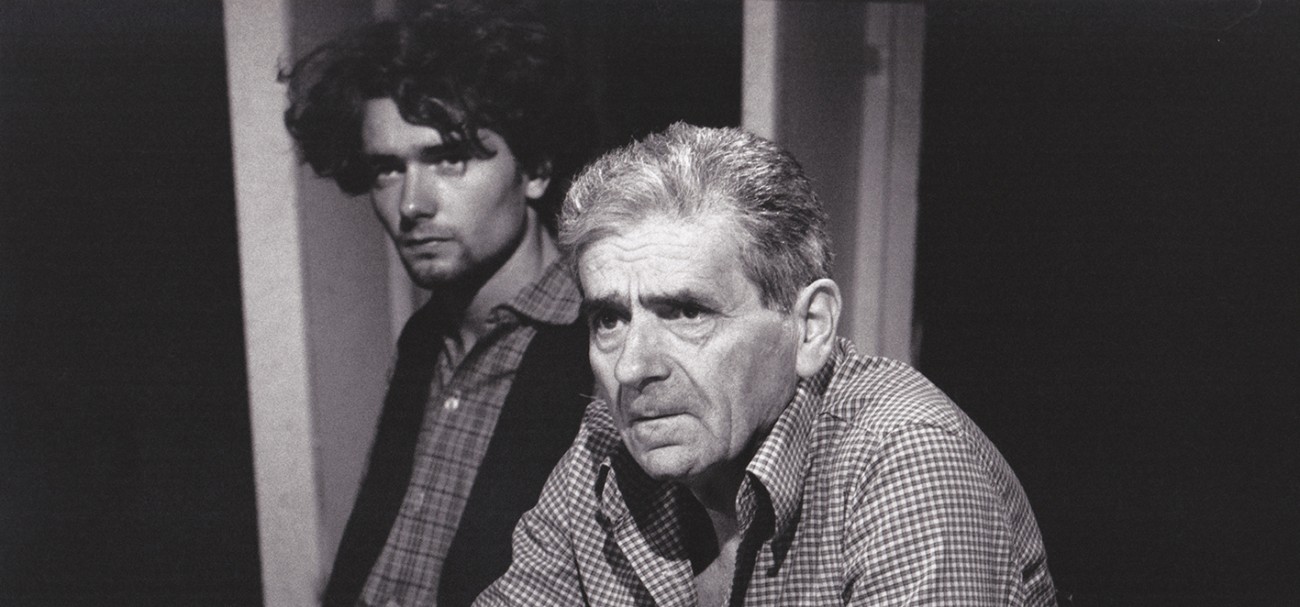

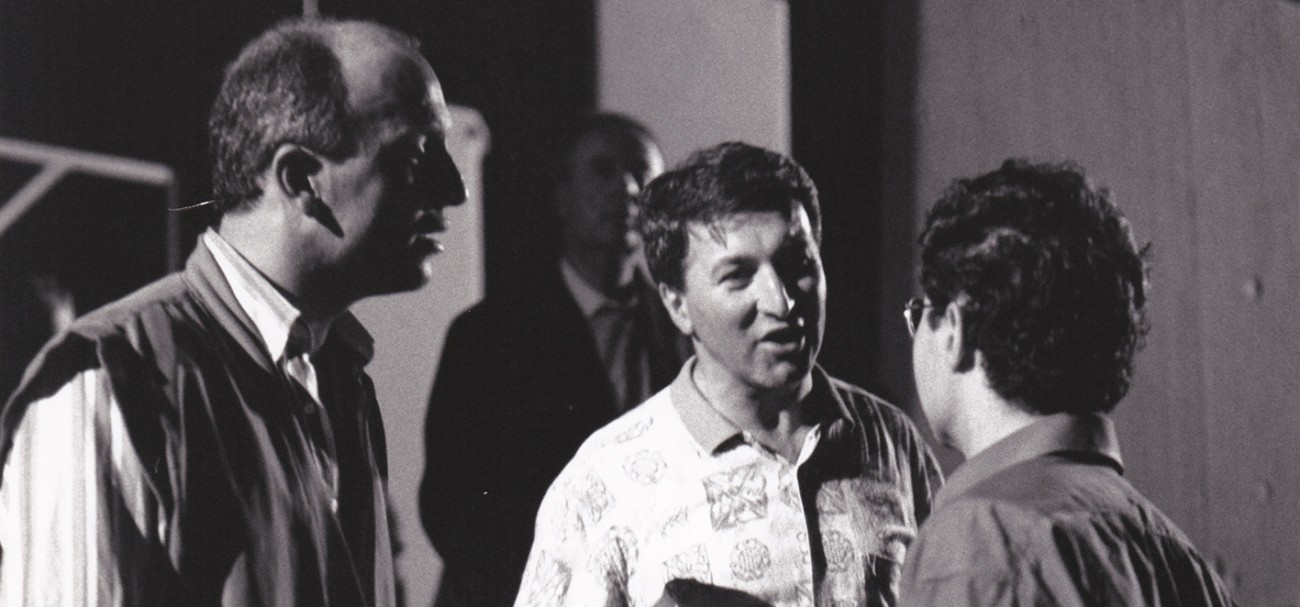

Watching all this was a group of contemporary ‘outcasts’: Italian unemployed and foreign migrants, people whom the modern economy was depriving of work and of a home. The outcasts came into direct confrontation and conflict with the Monticchiello actors. Why was this stage used only to represent social and political issues from the past? Why could an autodramma not deal directly with the real urgent problems of the present day?

The initial reaction of the actors was shown as being defensive: they shut themselves away from these inconvenient questions. But they were persuaded to open up again, and to communicate with their critics. They still suggested that old-fashioned peasant solidarity could be relevant to the present; and insisted also on the value of subversive fantasy presented on stage. In fact the autodramma concluded with a scene from a ‘world turned upside down’, in which the peasant family evicted their landlord.